I’ve written previously that Consumer Psychology is very difficult to understand. For example, why do longer lines counter-intuitively create even more demand in restaurants? Consumers are weird.

This is the biggest reason why I personally avoid building in consumer tech – though I do agree that the biggest companies are all, in some ways, consumer-facing.

The biggest skill in consumer startups is the skill of having good taste, and upon reflection, I don’t think I have a good-taste-alarm-bell within my head.

Anyways, I bring up my old post on consumer psychology is because I’ve noticed another example of a unintuitive human quirk that complicates my understanding of consumer psychology! That is, depending on the person, one tends to either signal (flex their status) or countersignal (not flex their status).

In this post, I note how bizarre it is for Dyson to be successful in making trendy vacuum cleaners and premium bladeless hair dryers. Whoever did the growth and marketing at Dyson deserves a raise, because those people convinced millions of humans to shell out $300 for a fan that just blows air in a cool way.

I mean, do people really care about their hair dryers being bladeless? And from an engineering perspective, the bladeless fan design results in less airflow compared to traditional bladed fans. But damn if they don’t look like they belong on the Death Star.

And that’s why they sell.

And there they sit on bathroom counters across America, with people showing off their Bladeless Dyson in morning routines like they’re luxury jewelry. My previous and simple explanation assumed that people are partly irrational in buying this product, and hence my point stands: Consumer Psychology is hard to understand!

I still think the latter is true, but I’ve been exploring this topic in my mind and now actually do not think people are irrational in buying these bladeless hair dryers.

Humans are innately status hoarders and observers. One is not concerned about the Dyson’s airflow as much as it functioning as a message to every houseguest about your status in the world.

And from the perspective of a evolutionist, it’s quite natural that we don’t want to think for ourselves. (I feel relieved when someone takes charge in a group project.) We can save time and energy by imitating others in perceived power positions; your signaling tells me how much I should trust and listen to you.

Even children bias towards those with prestige/status. For one, they’re more likely to imitate an adult that other adults regard as being higher social status! In experiments, children also tend to prioritize high prestige/status individuals when distributing valuable resources, a clear indication of a child’s implicit understanding of social dynamics.

Going back to the Bladeless Dyson, I honestly believe I never would have had the taste to design such a product. To predict that people will buy a hair dryer as a status of signal, to purposely center the design around an inefficient form factor, and to market it as a luxury item, is quite an interesting angle to sell an ordinary product. Who the hell wakes up one morning and rationally thinks, “You know what the world needs? A hair dryer that costs four times more and works slightly worse, but designed like it belongs in Star Wars!”

I want to expand further on luxury items here, because it seems that only luxury goods are products that are sold with the purpose of conveying status over any other function! (Fun fact, from my ECON0100 class, they are also known as Veblen goods.)

Let’s take luxury clothing and accessory brands as an example – women with Hermès bags and men with Rolex watches comes to mind. But this initial intuition struck me as odd. There are just too many people I know who own Hermès bags or Gucci glasses. Maybe that’s because I happen to know so many privileged people, but if it was truly a status of the elite, I would expect the number of people to have such luxury goods to be drastically less, perhaps by a factor of 10X. If a “luxury” brand props up a store in my nearby suburban mall outing, is it really luxury?

Turns out, questioning this intuition is correct. Contrary to my belief, Hermès and Rolex are actually not for the elite! Though they may have once started as brands for the elite (Hermès initially sold only to European royalty and oil barons), these companies essentially scaled themselves out of scarcity in their success, eventually enabling the average, slightly-upper middle class family to afford.

If they can flaunt their Hermès and Rolex, what do the families with private jets flaunt?

Different wealth classes play entirely different signaling games.

Let’s focus on just two.

The first wealth class are the rich families. The ones with big houses and Porsche cars. I’ll call them the nouveau riche (French for new money), as families who can live comfortably enough to recognize their position in society. Anecdotally, I find that this class tends to flaunt their luxury.

Or in relevance to this blog, they signal. They wear brands that signal to the mass public that they are wealthy. The obvious brands come to mind: Rolex, Hermès, Gucci, Hugo Boss, Louis Vuitton, Channel, Dior, and so on.

The second wealth class are the ultra-rich. The ones who own private jets and super yachts. Oppositely, they countersignal. They inevitably develop restricted codes, intelligible only to initiates. Only other wealthy families, with cultural capital accumulated over generations, can recognize a nondescript brand’s significance. Thus, they wear brands that signal to only other ultra-rich families that they are wealthy (or high-signal) seem otherwise normal to the average person.

These select brands are embedded in tacit knowledge, learned through elite boarding schools or private clubs. A Nantucket Reds wearer signals not wealth per se, but biographical authenticity. Summers on Martha’s Vineyard, sailing heritage, WASP cultural fluency, etc. It’s status derives from its sense of uncodifiability, as you simply do not stumble your way into understanding why Nantucket Reds or certain Belgian loafers carry elite status for the same reason why you cannot understand why a mid-range Subzero fridge is considered elite but not the latest and most expensive LG fridge equipped with a touchscreen panel and real-time cameras on the inside.

For certain categories of goods that have both low-cost and high-cost options, disruptive selection occurs for the wealthy, creating a dead-zone that is avoided.

Example 1: cars. Wealthy people either daily drive a cheap and reliable Toyota under 400,000 Bugatti. There is no “middle” option for them – only middle-class (but not ultra-wealthy!) posers who want to show off their perceived wealth will purchase a low-end Porsche model.

Example 2: men’s suits. Wealthy people either show up casually dressed (without a suit) or with a 100 suit from Macy’s.

A very vanilla, middle of the pack option for these goods is actually an anti-signal!

A question for you now, who is statistically an average reader (and not ultra-rich): ever heard of Patek Philippe? Matsuda eyewear? Blublocker glasses? Mouawad jewelry?

If you’re sitting there on your bed or chair going “what the fuck is Matsuda eyewear,” then you’ve proven my point. These are brands that casually charge $50,000 for a wristwatch or charge more for sunglasses than most people spend on a cheap car.

(By the way, if you knew every single brand, please let me know so I can be your friend.)

They’re the real luxury brands. They’re the brands the billionaires wear. They’re the ones they don’t want you to know.

The irony here is that your blank stare is exactly what makes these brands so elite. While every Instagram influencer flashes Gucci logos in your face, true wealth communicates status through a completely different frequency that flies right over the heads of 99% of the population.

Compare this Mouawad bag:

With this Dior bag:

One has a huge logo, recognizable for the masses at a glance. The other looks expensive, but has no logos.

The nouveau riche shouts; the ultra-rich whispers.

The nouveau riche signals; the ultra-rich countersignals.

We can extrapolate this countersignaling theory to other scenarios.

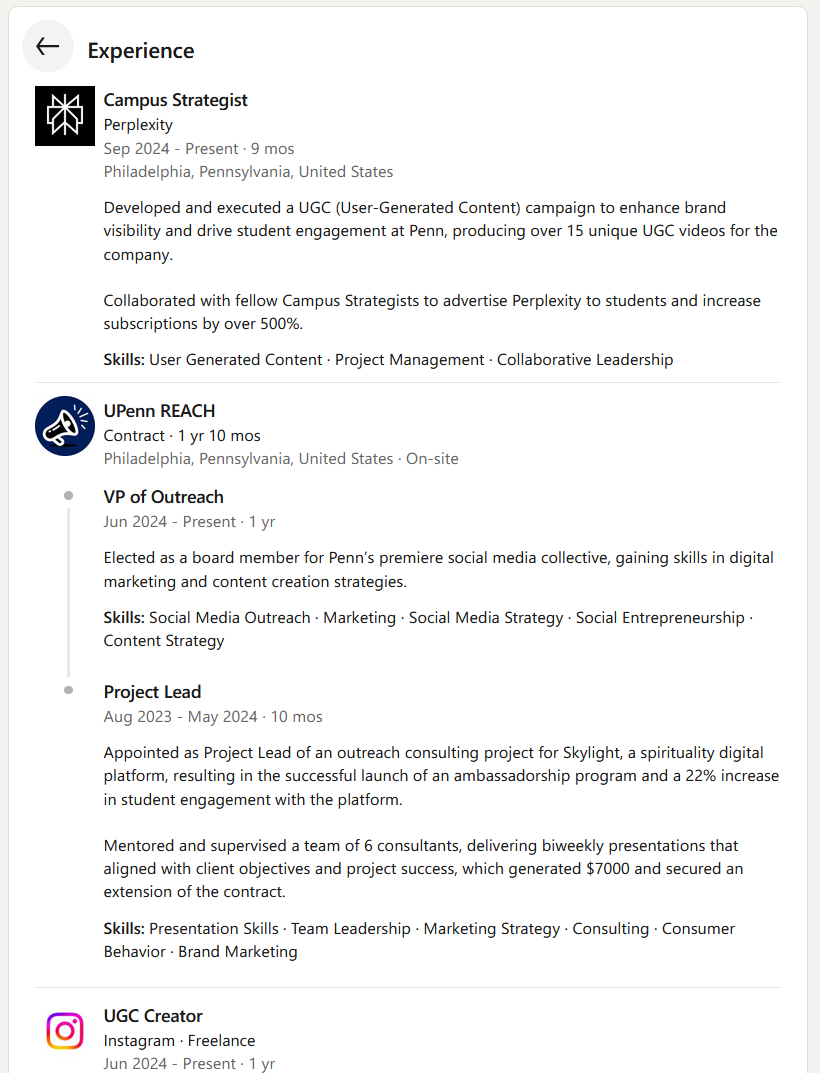

There are students who put “Goldman Sachs” on their LinkedIn after they were invited to a Goldman Sachs sponsored virtual summit. Or the students who are happy to announce that they’ve become a Perplexity Campus Strategist for their campus. Or worse, students who put a school club with ten other members as real-world managing experience.

Mediocre students try to signal as much as possible to show that they are the best.

But to the top recruiters I’ve spoken to, those signals are merely hollow posturing. Empty shells, wrapped in nice sounding titles.

It is the top students who shy away from the spotlight. Across all the incredible engineers and thinkers I’ve met, they generally share a strong sense of self-belief in themselves. My takeaway (as a student myself) is that only a student who is truly confident about their skills can afford to avoid the signaling game, because their status is already well-known or inferred from other sources.

Stealth is an exclusivity signal.

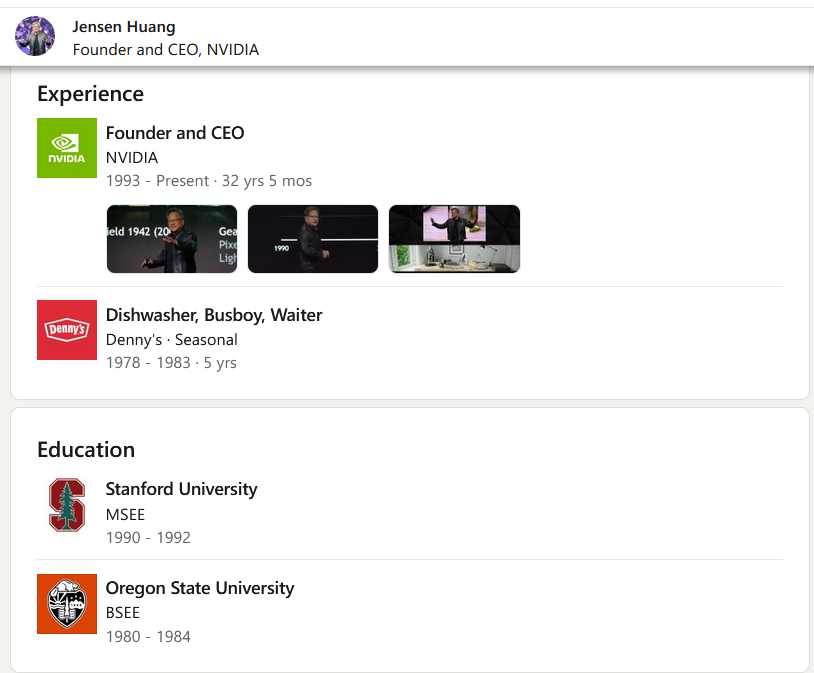

On a whim, I checked out Jensen Huang’s LinkedIn, and what do you know? He countersignals!

Just two experiences, one of which starts with “Dishwasher.” No activities or clubs from his days at Oregon State or Stanford.

Now let’s look at a student at Penn. Of the eight experiences, one is a Perplexity “Campus Strategist,” four are Penn clubs, and one is a self-run Instagram account.

Novices signal because they lack track records; experts countersignal because their reputation precedes them.

To end off, some advice targeted for other students: don’t attempt to signal everything! If you have a few great internships (SpaceX, ASML, DeepMind, or likely the other companies on my list), isolate those experiences instead of filling your LinkedIn with your time at Mathnasium tutoring some kids in algebra.

Adding more does not make it better: people judge the average of your achievements, not the cumulative. That SpaceX internship will become mentally diluted when it’s sandwiched between with a low-status company. If you add low-signal companies with that one high-signal company, your brain may see it as “more experience!” but to a recruiter, it whispers “mediocre overachiever trying too hard to impress.”

Treat your profile like an art galleries, not storage units. Every experience displayed should have earned its place.

Countersignal.