I’m currently working on two main projects at the moment (both in stealth), but one is in information theory and the brain, and the second is in personal relationships. Serendipitously, it has gotten me to think about information entropy and how it relates with interpersonal relationships, which inspired this post.

Information lies on a spectrum of being low-entropy or high-entropy. Take for example, this string of text:

aaaaaa

This information is low entropy because you can easily predict the next letter, which is likely just another a.

This text, however, has slightly higher entropy:

aabbcc

It’s slightly harder to predict, but still doable.

Meanwhile, this text has a very high entropy:

1gF!%sA

It is impossible to predict.

In a more realistic setting, a sentence like “The sky is blue” is low entropy. It’s something you could have predicted, because your mental model of the world is that the sky is, well, blue.

Unfortunately, most conversations and ideas are low-entropy. For starters, most conversations I’ve had in my life do not go on and change my life or way of thinking. I guarantee it to be true for you as well. In essence, most ideas are easily predictable by your own mental models of the world, and therefore does not add new information. Just take a look at most productivity blogs – the advice (information) given is highly predictable. Get sleep! Exercise! Deep work! Time chunk!

Having codified this, it immediately makes sense to me the type of ideas and writings I want to produce and come more in contact with: information that is high-entropy. Information that makes me think, information that makes me pause for a bit and breaks my prior worldviews. Sentences so beautifully crafted, ideas so interconnected, that it remains in my brain long after I’ve closed the tab I read the blog on.

The reasonable first step to me is to find people who are high-entropy themselves who are able to consistently output high-entropy work. But this is slightly difficult to do. After all, how many people do you know who you can confidently claim as high-entropy?

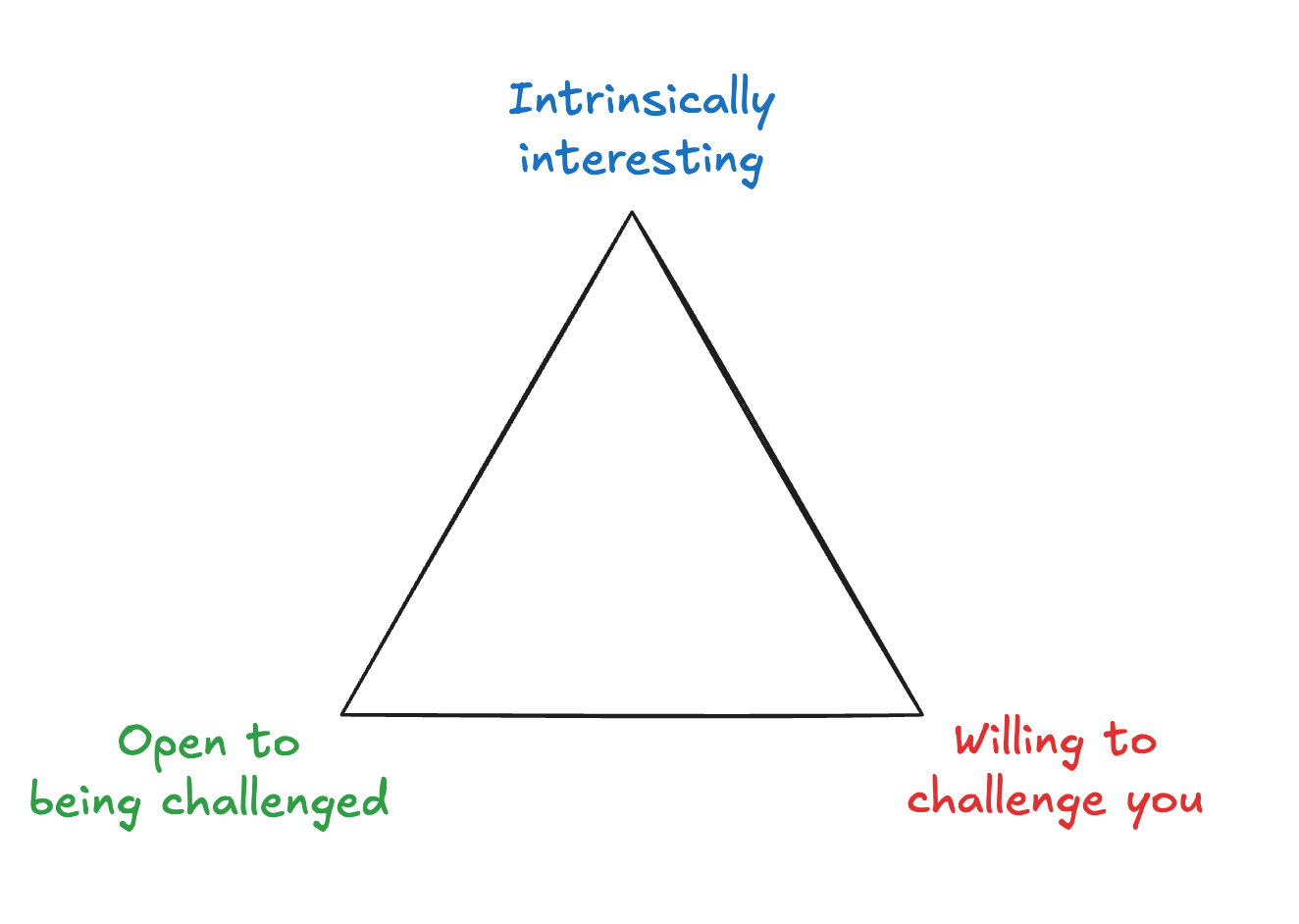

It’s easier to find such people if you know what you’re looking for. As such, I define these “intellectual processors” as having a rare (?) mix of traits such that they:

- Hold high-entropy information

- Have the capability to challenge your views

- Are open to challenges to their own views, or what I deem cognitively flexible.

Each trait is rarely manifested in an individual.

#1 is rare because most people don’t seek out high-entropy information! This type of information is hard to obtain by virtue of it being unpredictable and novel in the first place, but more importantly, my mental model of most people is that they are comfortable knowing that they don’t know something. This makes it really difficult to seek out critiques of your opinions. Why do so? Whereas there are people who are very much uncomfortable with what they don’t know. Knowing that the unknown exists is a scary emotion for them, and they seek to lessen that for self-comfort. To them, it mentally hurts to remain ignorant.

(This reminded me of what I wrote previously in Principles: I always want to form opinions on things, and then find the strongest critique of those opinions.)

#2 is rare because high-entropy information often conflicts with another person’s worldviews. High-entropy information is often critique, and people do not like to critique others. In fact, it’s a societal sin to criticize and a societal good to praise. (From my recent readings of mimesis, it’s accurate to classify criticism as anti-mimetic and praise as mimetic… interesting) Maybe criticize is too harsh of a word here, but I find even feedback is rarely given unless explicitly asked. Rationally, this is surprising. Praise tells you nothing new (low entropy, minimal update), feedback tells you everything new (high entropy, maximal update).

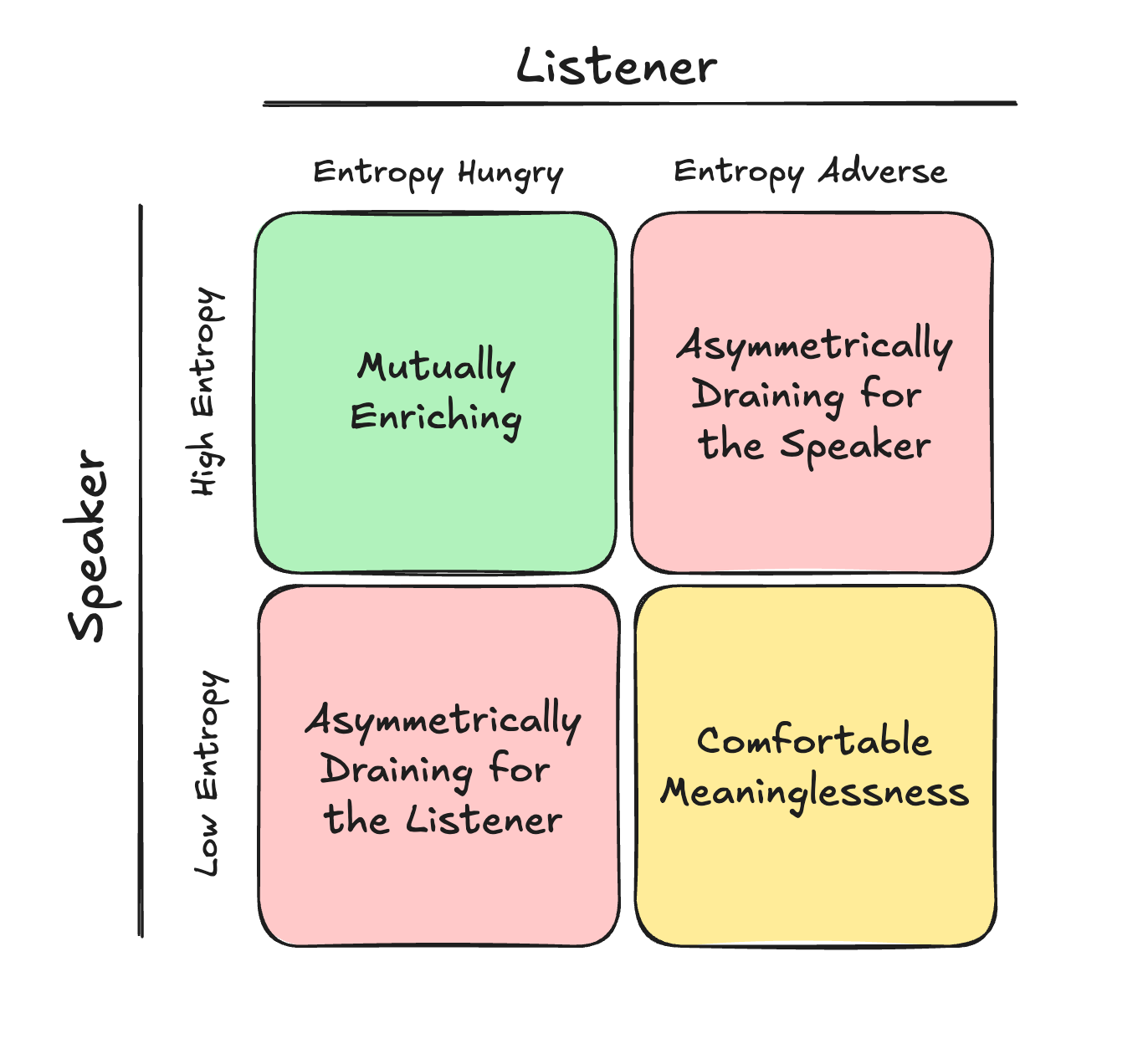

And from my notes on the been-in-drafts-for-10-months idea of systems being trapped in inferior equlibra, perhaps this too, is another example of society being trapped. I imagine people want to have mutually enriching conversations, but a majority of people are both low-entropy speakers and entropy-adverse listeners. Paired with an average individual, conversational autopilot takes over and what you get is a comfortably meaningless conversation – a form of social elevator music.

I also don’t believe low-entropy speakers with entropy-hungry listeners and vice versa sustain themselves for very long. For example, a very interesting individual would not want to talk with someone who is opposed to, or does not entertain novel ideas. Likewise, an entropy-hungry listener wants interesting takes, but cannot receive them from someone who knows nothing interesting. In both cases, conversations fizzle out.

I’m cautious to claim that there is some sort of coordination failure occurring here. Everyone would prefer the green quadrant – intellectually stimulating conversations that is deep talk – but reaching that requires to become a high-entropy speaker first, and someone else to drop their cognitive defenses to become entropy-hungry.

Neither move feels safe individually, so we default to pleasant, hollow conversations instead of deep conversations that we all crave for.

#3 is rare because people like to right over correct. Conversely, people who are cognitively flexible can adopt any position, even when it was not their original position, if it is clearly the better one. Or in other words, I like people who bend their theories to the data, not the data to their theories. These people are truthseekers and willing to accept critique.

To sum up, being good at all three skills is rare. The combination of people who have interesting ideas, can give critique or push back on ideas despite societal pressure, and is actively open to receiving critique and updating their mental models is a small subset, but everyone within that subset are very interesting people in their own right.

Most of us excel at one or two dimension while failing the others. I know brilliant thinkers who can’t handle pushback on their ideas. I know people who crave intellectual stimulation but contribute little novel thinking themselves. I know those brave enough to critique others but who operate from rigid worldviews. And so on.

Anecdotally, looking at my personal CRM (which is just a spreadsheet – someone needs to build a better solution!), I find it interesting that the people I hold the highest regard for are those who somewhat fit in all three categories. I just love talking to those people; I can even recall specific instances in which their conversation have shaped the way I think.

Unfortunately, I find most people aren’t good at all three (myself likely included, though I need other people’s opinions.) Here’s some examples:

- If you’re weak at #1 (don’t have high-entropy/interesting ideas), you’re just boring. It’s just that conversations with you are sterile and shallow.

- If you’re weak at #2 (can’t give critique or push back on people), you’re easy to talk to. Conversations become pleasant, but never intellectually stimulating, because they never challenge you.

- If you’re weak at #3 (can’t update mental models with new information), you’re adversarially stubborn and just extremely annoying to talk to.

Wait what?

What surprised me when thinking through this is that if you’re specifically missing one of the three traits, it makes interacting with you miserable.

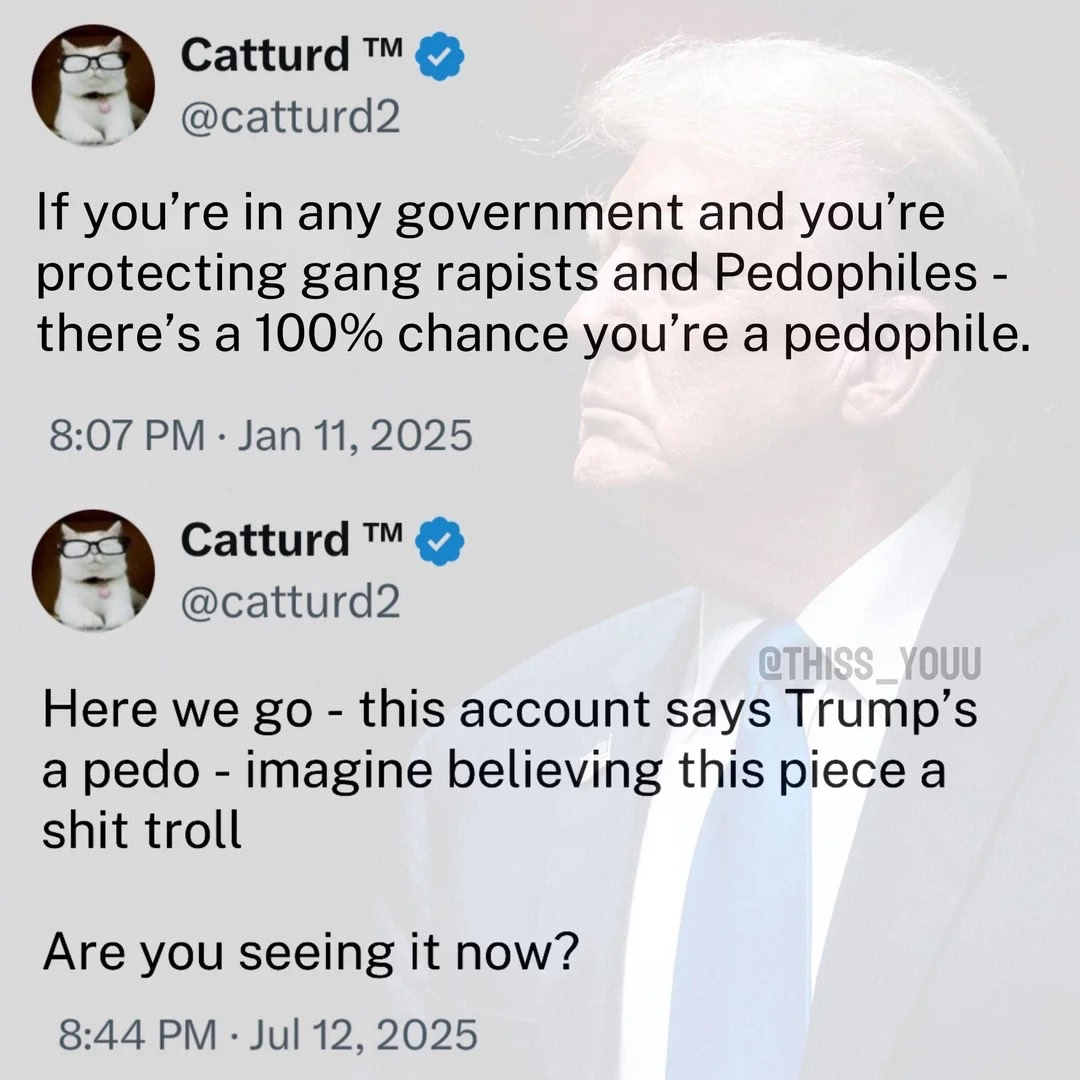

Worst of all are the people who seemingly cannot update on new information. People who cannot change. People who bend data to their theories. We all know people like that. An obvious example is a die-hard MAGA fan (versus a rational Republican) and the current Epstein files situation.

These people are insufferable and impossible to talk to. It’s worse than being stubborn – there’s almost a sense that these people talk right past you.

A common phrase in the venture world that people parrot is “strong opinions, weakly held.” The problem with this is that it implies people consciously understand the probabilities they assign to their opinions. People don’t.

Most people don’t run Bayesian calculations in their heads, but a simpler categorical sorting: good, bad, and irrevalent. Yes, no, maybe. Accept, reject, ignore. Instead of a continuous spectrum of opinion evaluation, it becomes discrete. As such, updating mental models becomes nearly impossible because any new information has to have a sizable step-function influence on us to shift from one category to another, rather than nudging strengths along a line.

Adversely, the phrase “strong opinions weakly held” has just bred a group of people who are stubborn while unreasonably justifying their stubbornness. An example conversation that happened to me:

Maxx: “So you’re trying to build a community for managing personal debt finances…?”

Alice: “Yep! People want to belong somewhere, and personal finance is a huge market. Look at Discord, gamers wanted to belong to a community and that’s why it succeeded.”

Maxx: “But personal finance apps are inherently private behavior. No one wants to publicly share their financial struggles. Discord worked because gaming was already social, I feel like you’re trying to make antisocial behavior social and that’s not going to work.”

Alice: “You’re overthinking it. If we build it, they will come. Look at how unexpected TikTok’s success was, no one predicted that it’s short-form video content would completely dominate over Instagram and Snapchat.”

Maxx: “Okay but like TikTok is fun. Producers get dopamine from attention, and viewers get dopamine from watching funny content. There’s a viral loop here. Your users would be sharing their financial anxiety and debt. That’s the opposite of status signaling.”

Alice: “That’s such a narrow view of human psychology. You don’t even have TikTok or Instagram, who the hell only uses LinkedIn and X? Maybe you just don’t understand how millennials and Gen Z think about money differently than previous generations.”

Maxx: “It’s basic consumer psychology. I also want to point out that Discord succeeded by solving realtime voice-chat problems for gamers before becoming a community aggregate platform. What problem are you solving?”

Alice: “So now you’re some expert on consumer behavior just because you wrote two blog pieces on it?”

Maxx: “Well, no, but I also know a guy who tried to do the exact same thing and it failed. People don’t want to share that they’re $8 away from bankruptcy.”

Alice: “That’s completely different. My friend posts about her student loans on Instagram all the time.”

Maxx: “But one person doesn’t validate market demand. Have you talked to other potential users?”

Alice: “Surveys aren’t actually that useful though. I read the Steve Job’s biography and he said that customers don’t know what they want. My intuition tells me this will work.”

Maxx: “Ok, but Jobs had years of product development before the iPhone and iPod came around. What’s your experience?”

Alice: “Experience is also overrated. Fresh perspectives disrupt entrenched industries… did you know that Patrick Collison started Stripe without having worked in banking or financial services?”

Maxx: “Okay fair, but going back to my point earlier, Discord succeeded by solving real problems gamers faced, like amazing real-time voice chat. What specific problem are you solving? I don’t think you’re solving anything to be honest.”

Alice: “This is exactly the kind of pessimistic thinking that would have killed Instagram before it launched. You probably would have said photo-sharing wasn’t a real problem too. I’m not going to listen to a guy who’s never built a consumer product before. Real entrepreneurs follow their gut.”

Here, Alice ignores the specific claims that Maxx makes and dismisses it with phrases like “that’s boomer behavior” or “I’m not going to listen to you because you haven’t built in consumer.” Talking with people who are unreasonably stubborn is like talking to someone who counters with irrevalent points: they don’t even listen to your actual arguments! The problem with “strong opinions, weakly held” is that it just becomes “strong opinions, strongly held.”

Whereas justified stubbornness is acceptable:

Maxx: “If we don’t do anything about climate change by 2050, we’re fucked.”

Alice: “I disagree, climate models have systematically overestimated global warming for many decades. I don’t think it’s as big of a problem as we make it to be.”

Maxx: “But CO2 levels are currently the highest in human history. The greenhouse effect is basic physics and you can’t argue with that!”

Alice: “Sure, CO2 traps heat. But climate sensitivity keeps getting revised downwards, and even IPCC’s own forecasts show a huge uncertainty range. Every doomsday tipping point prediction has been completely wrong, and this 2050 timeline is probably wrong as well. I don’t think any major deviations will occur based on current projections.”

Maxx: “Look at this data on coral bleaching, ocean temperatures, and acidity then! Climate change will destroy natural reefs to start!”

Alice: “Okay, but corals have survived much warmer periods in Earth’s history when CO2 levels were double what we have right now. This could be a natural cycle. You don’t know what you don’t know.”

Maxx: (Visibly annoyed) “I can’t believe you’re a climate change disbeliever!”

This scenario is perfectly realistic to me. I’ve been doing my own research on climate change (given my interest in it and marine ecosystems), and it actually does seem that timelines are overblown! Yes, we should work on climate change. But is it a doomsday scenario? I think not! Keep in mind the incentives behind those who purport the doomsday scenario. Writers optimize for attention, not accuracy. I suspect there is a large incentive here to evoke a doomsday sentiment around climate change to get people to act.

In startups, everything is uncertain, so to some degree, you need to trust your gut. But you need to think about increasing the odds of success per bet whenever possible.

Unsuccessful entrepreneurs refuse to engage with information that conflicts with their mental models of the world and problem space. Successful entrepreneurs actively incorporate the information they receive to update their mental models of the world.

It’s interesting to note that Jensen Huang has a term he uses called LUA, which stands for “Listen to the question, understand the question, answer the question.” This weeds out people who put up abstractions to deflect an answer to a question.

High-entropy is a gift. Criticism is a gift. Getting direct feedback and information that updates how you view the world is continuous improvement. It’s up to you as to the degree that the feedback will affect the way you live your life.